‘…events can only be narrated, while structures can only be described’ (Postlewait 2009, 2)

According to Postlewait, all events are ‘illustrations of the theory, which defines the context and controls the interpretation’ (2). Postlewait is of course referring to theatre history. Theatre as we already know from my previous blogs is ephemeral. We are in the moment whenever we see a performance and that particular moment will forever be planted in our memory. Historiography however, can change all of that. Historiography is defined as ‘etymologically (…) the writing of history’ (Jones, 2014). Since we cannot fully explain to others how aesthetically engaged we were after viewing a performance, other sources such as reviews, journals are available for us to understand just how good or bad a performance can be. However, the 21st century has unveiled a new concept of viewing a performance without actually ever attending it physically. In a previous blog, I mentioned live broadcasts and live recordings. These concepts allow users to watch a performance through a different scope, such as a television recording or a live stream online. Whilst this can save you money on time and travel, it does tend to have a few disadvantages. For example, you are viewing a performance through the eyes of another person, meaning that you will not be able to experience the liveness of attending a performance physically. There is also the possibility of signal interruptions in connectivity between you and the server if you are experience a live performance online.

However, live recordings and broadcasts can be beneficial in some cases (this is where Postlewait’s theory at the beginning comes into fruition). A recent production of John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi was performed at the Globe’s Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, and was performed in front of a live audience whilst recorded live and later broadcast as a BBC programme.

The production was intended to be a replica of a typical Jacobean staging, which involved the inclusion of candles as lighting for the stage (which cost around £400 a show). Whilst the staging of The Duchess of Malfi was considered near enough authentic as when it was first performed in 1614, this particular production had a number of flaws. For instance, the candles were considered a problem from the very beginning, as audiences found it very discomforting to sit through an entire performance whilst soaking in sweat. In fact, members of the audience were warned by ushers to leave their coats in the cloakroom because it had turned out to be ‘so hot in there’ (Lawson, 2014). In addition to this, the audience were seated in the traditional format of wooden benches, to replicate how audiences sat during a traditional Jacobean production:

‘The stepped wooden benches are also relentlessly uncomfortable: no one who has a deep personal concern with both theatre of the Shakespearean era and the management of long term sciatica should risk the Wanamaker’ (2014).

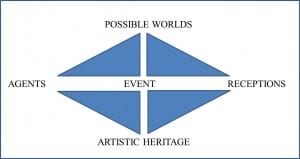

This particular example brings us back to Postlewait’s theory as noted at the beginning of the blog. However, to further elaborate on Theatre Historiography, here is a Postlewait’s model which examines the relationship between the theatrical event and its context.

As we can see, Postlewait’s model depicts various aspects of the context of a theatrical event, in order to understand the relationship between the two, ‘…each of these four factors – world, agents, receptions, and artistic heritage – need to be understood as part of the even as well as part of the context’ (Postlewait 2009, pp.14-15). Each triangle found in the model marks as connection between each aspect of context, linking (1) agent, world, agent; (2) agent, artistic heritage, event; (3) audience, world, event; and (4) audience, artistic heritage, event. (17). In addition to this, the 90 degree angles of each triangle must meet at the central event i.e. (1) agents and event; (2) world and events: (3) audiences and events; and (4) artistic heritage and event (17).

With Postlewait’s theory and model into account along with Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi contemporary approach, it’s amazing to believe that no matter what approach a particular narrative takes, the structure can always be etched in theatre history!

Works Cited:

Jones, Kelly (2014) The Contemporary in Historical Contexts 1 [lecture] Current Issues in Drama, Theatre and Performance DRA9020M-1415, University of Lincoln, 19 November.

Lawson, Mark (2014) Globe’s Sam Wanamaker Playhouse casts new light on Jacobean staging. [online] The Guardian. Available from http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/jan/20/globe-sam-wanamaker-playhouse-light-jacobean-staging. [Accessed 27 January 2015].

Postlewait, Thomas (2009) Unmarked: the politics of performance. London: Routledge.