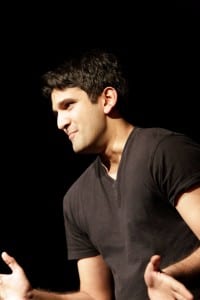

After our initial performance showcase were postponed for a month due to scheduling difficulties, I am quite relieved to say that I have finally been able to perform (on two occasions I might add!) in front of a live audience. More so, I was proud to have been able to perform my performances as part of the Newvolutions festival, an occasion that I have always wanted to be a part of but was never a part of during my tenure as an undergraduate until a week ago.

I was a little apprehensive on how exactly I was supposed to introduce my performance piece to the audience. At first, I had decided on starting the performance immediately, and then perhaps explain my aim for this performance to everyone. However, I made a last minute decision on how I should address the audience. In the end, I felt compelled to explain to the audience that this performance is more of an experiment with liveness and mediation and that they should shift their focus between my face and the projection of quotations. I believe this was the best approach to acknowledge what my aims were for this performance, in order for the audience to avoid feeling lost and confused at what is transpiring on stage.

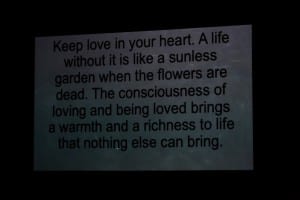

I was very particular with which quotations would suit best for my performance. Each quotation used had a specific mood or emotion. In some ways, it was a blatant move on my behalf, just so I can convey the emotion clearly for the audience. However, I was hoping to cause some means of controversy by selecting a distinct, notorious figure, to create a juxtaposition between the quotation and source. Here are the quotations along with the authors who wrote them in the order they were presented at the performance:

‘There comes a time in the lives of those destined for greatness when we must stand before the mirror of meaning and ask: Why, having been endowed with the courageous heart of a lion, do we live as mice?’ – Brendon Burchard

‘Believers, be mindful to God, speak in a direct fashion and to good purpose, and He will put your deeds right for you and forgive you your sins.’ – Osama Bin Laden

‘Keep love in your heart. A life without it is like a sunless garden when the flowers are dead. The consciousness of loving and being loved brings a warmth and a richness to life that nothing else can bring.’ – Oscar Wilde

‘Older men declare war. But it is youth that must fight and die.’ – Herbert Hoover

I hope each quotation had a clear emphasis on the emotion or mood I was hoping for. If not, here is a brief outline on the emotion I was going for:

Quote 1. – Motivational

Quote 2. – Religious

Quote 3. – Love

Quote 4. – Grievance

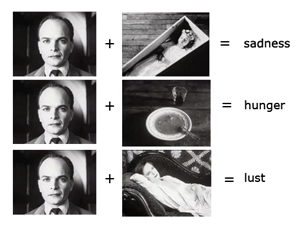

I certainly do hope that I have succeeded in replicating The Kuleshov Effect using different techniques and ideas. If I had the chance to perform this piece again however, I would certainly try and mediate the entire performance rather than perform it live, just so I can experiment with the level of conveyance of emotion using a different form.

Thank you to everyone who saw our MA Drama Showcase during the Newvolutions festival, and I congratulate everyone who took part in it. I also thank the tech team for their help throughout the day.

Also a big thank you to Phil Crow for the pictures. For the entire photo album of the MA Drama Showcase as well as his portfolio, click here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/61839232%40N02/sets/72157650394311512/