Post-dramatic theatre, is a concept suggested by theatre researcher Hans-Thies Lehmann, which explores the relationship between drama and the ‘no longer dramatic forms of theatre that have emerged since the 1970s’ (2006, 1) which during that period, media technology had proliferated. According to Lehmann, this relationship has often been neglected or ‘under-explored’, and have somehow been referred to as ‘postmodern’ by those who have approached these new dramatic forms (1). Prior to the publication of Postdramatic Theatre in 1999, Lehmann had already set himself to find a language for these ‘new theatre forms’ by ‘systematically considering their relation to dramatic theory and theatre history, including their resonances with (and divergences from) the historical theatre avant-gardes’ (1). The term ‘post’ however, is not defined as rejecting the drama, but Lehmann utilises the term to emphasise that the drama is taking new forms,

‘…’post’ here is to be understood neither as an epochal category, nor simply as a chronological ‘after’ drama, a ‘forgetting’ of the dramatic ‘past’, but rather as a rupture and a beyond that continue to entertain relationships with drama and are in many ways an analysis and ‘anamnesis’ of drama’ (2).

In order for me to gain a clearer picture on how postdramatic theatre works, I took it upon myself to read Dan Rebellato’s When We Talk of Horses: Or, what do we see when we see a play? Reballato’s paper provides an interesting insight on Lehmann’s theory of postdramatic theatre, by describing his experience with plays:

‘…How I read a play. I don’t simply read it as words on a page, but I couldn’t really say that I produce particularly vivid mental images, that inwardly I am transformed into a grand theatre in which these characters and their actions come to life…When we go to the theatre, what are we looking at? How does that relate to the fictional world being represented? Do we take what we see on stage as a visual representation of the fictional world? How vividly are we to fill in the gaps in the performance?’ (2009, 17).

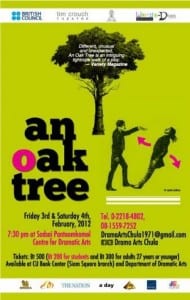

Reballato’s essay is quite interesting, particularly when it can physically come into fruition with another play. Fortunately, there is such a play that utilises Reballato’s theory. Tim Crouch’s An Oak Tree has proven to be that play which conforms to these new dramatic forms that Lehmann was referring to.

An Oak Tree centres on a father’s grief after the loss of his teenage daughter in a traffic accident. Crouch’s play deals more on instructing the actor to perform the play in a certain direction in front of an audience. The catch however, is that the actor is unable to improvise and must abide by the requirements of the director during the performance. This is mainly due to Crouch’s approach to these dramatic forms similar to Lehmann’s theory, ‘Crouch demonstrated that the theatre space, together with the performance of written dialogue spoken within it, had transformational possibilities potentially exceeding those of the gallery’ (Bottoms, 2009, 65). Having received a number of accolades for his production, Crouch has succeeded in portraying these dramatic forms whilst establishing a narrative at the same time in An Oak Tree.

Works Cited:

Bottoms, Stephen (2009) ‘Authorising the Audience: The conceptual drama of Tim Crouch’ in Performance Research, 14(1), pp. 65 -76.

Lehmann, Hans, L. (2006) Postdramatic Theatre. London: Routledge.

Reballato, Dan (2009) ‘When We Talk of Horses: Or what do we see when we see a play?’ in Performance Research, 14(1), pp. 17-28.